The Excavation Project

Naga was the southernmost city of the Kingdom of Meroe, a neighbour and powerful rival of Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt. Situated northeast of Khartum, the capital of the Republic of the Sudan, in the steppe far from the banks of the Nile, Naga has remained untouched since its heyday from 200 BC to 250 AD. Sprawling over a surface of approximately one square kilometre, this pristine site provides ideal conditions for archaeological research. The Egyptian Museum in Berlin excavated at Naga from 1995 to 2012 with the financial backing of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (the German Research Association); in 2013 the project was transferred to the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich.

A secondary royal residence for the kings and queens of Meroe, Naga was a city of splendour. Three of its temples have survived intact through the millennia, fifty more temples, palaces and administrative buildings, concealed under huge mounds of rubble, await excavation, along with the vast necropolis with its hundreds of graves.

With their mix of African, Egyptian and Hellenistic components, the abundant architectural remains, sculpture and reliefs found in Naga are a testimonial to Naga’s importance as a cultural bridge between Africa and the Mediterranean world.

© Naga-Projekt

© Naga-ProjektIts long-term restoration programme and the use of innovative 3-D technologies in the documentation of architecture and relief both make the Naga Project a pioneer in state-of-the-art archaeology.

A site museum is in the works to protect the large number of reliefs, statues and small finds. It is set to serve as a focus for the historical and cultural identity of the Sudan. The plans were generously donated by renowned British architect David Chipperfield; the Qatar Sudan Archaeological Project is financing construction, which is due to commence as soon as possible.

Discovery of the Site and Project History

1820-1995

The first Europeans to visit Naga – in 1822 – were two Frenchmen, L.M.A. Linant de Bellefonds and F. Caillaud. In 1844, the Prussian Expedition led by R. Lepsius documented all the monuments of the ancient city visible at the time. Nevertheless, Naga was to remained untouched for the next 150 years.

1995-2009

It was not until 1995 that the director of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, Dietrich Wildung, received an excavation license for Naga from the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums in recognition for the exhibitions on Ancient Sudan he had organised in cooperation with the Munich museum. Together with Lech Krzyzaniak of Posen, an archaeologist with many years of experience working in the Sudan, and the latter’s wife Karla Kröper, he began a long-term project financed by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation). By 2009, the Tempel of Amun, Tempel 200 and the Chapel of Hathor had all been excavated, documented and restored. Even though this work covered less than five percent of the city ruins, Naga proved to be a real treasure trove of architecture, relief and sculpture and is considered today one of the most interesting archaeological sites in the Sudan.

2013-today

In 2013, the Egyptian Museum in Munich took over the scientific and administrative oversight of the Naga Project. Excavations resumed in Fall of 2014.

Project Team

The overall administration of the Naga Project is currently incumbent to the director of the State Museum of Egyptian Art, Dr. Arnulf Schlüter.

From 1995 to 2021, the scientific direction of the Naga project was in the hands of Prof. Dr. Dietrich Wildung, who previously led the Munich East Delta excavation at Minshat Abu Omar (1977-1988) as director of the Egyptian Museum Munich (1975-1988) and developed the Naga project as director of the Egyptian Museum Berlin (1989-2009) since 1992. Since 2021, the leadership has been in the hands of Dr. Arnulf Schlüter, who has been a member of the Naga team since 2013.

Christian Perzlmeier has taken over the role of “Field Director” in 2020 from Dr. Karla Kröper (1995-2020) and is thus responsible for the work on site as excavation director.

All of the excavation work is accompanied and supported by colleagues from the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museum (NCAM).

Furthermore, archaeologists, architects and prehistorians from Germany, England, France, Canada and Poland are all a part of the scientific team.

The restorators from Restaurierung am Oberbaum GmbH are setting the standards for Sudanese archaeological projects. The Naga team, headed by Jan Hamann, has been working with the project for years.

This project is cutting-edge in its use of 3-D archaeological documentation using 3-D scanning technology. Thomas Bauer and his team from TrigonArt have not only measured and mapped each of the individual excavation sites, but also created a 3-D model of the entire area.

The workers on the excavation itself, about 70 in number, are recruited from the seminomadic peoples living within a several-kilometre radius around Naga. In order to sign for their salary, which they receive on a ten-day basis, they use their fingerprints.

Modern Archaeology

When it comes to specialists and equipment, the Naga research centre sets the standard for Sudanese archaeology and conservation work. The systematic use of a camera drone and 3D-scan technology for the documentation of the excavation site makes it possible to greatly optimize the publication of excavation results.

The subtle restoration of the excavated temples (without attempting to reconstruct absent areas) is supported by the Foreign Office and does justice to Naga’s status as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage site, preserving the general atmosphere of this “archaeological biotope”.

© Naga-Projekt

© Naga-Projekt3D Documentation at Naga

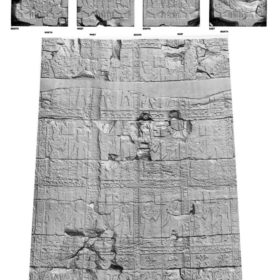

In view of the impressive sum of data collected through the systematic and objective 3D recording of finds, reliefs, columns, capitals and even whole temples, the Naga Project is a pioneer of three-dimensional archaeological inventorying. As early as 2005, various test projects confirmed the advantages of 3D scan technology and its manifold applications. Since then, it has become impossible to imagine archaeological documentation without 3D scanning.

© Naga-Projekt

© Naga-Projekt © Naga-Projekt

© Naga-Projekt © Naga-Projekt

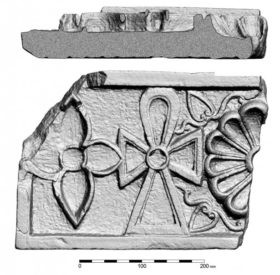

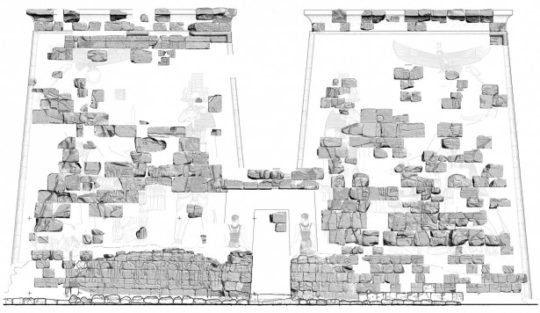

© Naga-ProjektStructured light 3-D scanning was not only used for the documentation of small finds: the excavation and documentation of 1,200 decorated blocks from Temple 200 took several seasons to complete. The goal was not only to document of each of the blocks in every detail, but also to reconstructo the relief decoration of the collapsed temple walls. Once each block had been scanned, it was possible to reconstruct the walls virtually.

The structured light scanner was also used for the Great Temple of Amun. In this case, it was not only a matter of repositioning fallen blocks, but also of documenting the imagery of the columns in the Hypostyle Hall: using correctional software, the data from the columns was flattened from a conical shape and morphed into to remove distortions – allowing the surface of the columns to be rendered into a flat relief. Special software was used to give the finished surfaces virtual light sources using special software in order to offer the best shadows for viewing, then exported as scaled visual data.

© Naga-Projekt

© Naga-Projekt © Naga-Projekt

© Naga-ProjektRestoration Concept

Everything we do leaves traces behind; everything we do causes change.

Naga represents a unique archaeological ensemble; an ancient landscape in need of preservation and, since 2014, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Every ancient building, every ruin in Naga is a monument of immense cultural and historical importance, requiring its own individual restoration concept.

From when it was first described by early travellers and the archaeological expeditions of Richard Lepsius (1844) and Breasted (1905-07) to the first excavations in the 1990s, very little change had come to Naga. But Naga is not uninhabited. The people living near the ancient city use the well at the centre of the site daily as a source of water for their animals and themselves. They, too, are an integral part of Naga and are a fundamental to any archaeological and restoration concept. Any kind of site management would be impossible without their help.

Archaeological excavations change the condition of a site, just as conservation and restoration work transform the site and its inventory of buildings and objects. Any action leaves traces behind. This is why it is so important to define how far the changes should go from the very beginning. The safety of the objects must always be the prime objective, the transformations should be kept as minimal as possible. The character and authenticity of the landscape must be preserved.

Archaeological excavations bring monuments and artefacts to light and expose architectural elements, making them more easily recognisable. Where before only a few stone blocks poked out of a picturesque, sand-blown landscape, now high walls rise, columns lie broken on the ground and mounds of huge stone blocks mark the spot where temples once stood. Other structures such as the Lion Temple and the Chapel of Hathor had never been entirely sanded in, withstanding two millennia in fairly good condition with only the lower courses covered in sand and sediment.

The goal for Naga is to preserve as much of the status quo as possible of the ensemble as well as its individual components. Changes or additions to the existing material should only be implemented when they are necessary for the preservation of the object, for example to improve the stability of the building.

These concepts are best illustrated in the restoration of the Chapel of Hathor. To help preserve the chapel, several structurally unsound capitals were replaced with copies made using the data from 3-D scanning. The copies are exact in every detail, making it possible to preserve the condition of the chapel before the removal of the unstable elements. In this way, the structural integrity of the building was restored without reconstructing the capitals or adding any modern materials such as struts or beams.

© Naga-Projekt

© Naga-ProjektTo achieve that goal, the upper courses of the building were disassembled, damaged and unsound elements carefully replaced with exact copies and the fabric of the structure stabilised using solidifying agents and specially-conceived materials before building the upper courses up again. All actions were meticulously documented and the state of the building and each of its components recorded in detail.

However, in real life not every theoretical concept can always be implemented to the letter. It is important to keep an open mind and adjust to new conditions as excavations proceed.

The basic concept behind the conservation of the historic records at Naga is to avoid reconstructions or anything that impacts on the atmosphere, such as protective roofing, information panels or tourist information maps, keeping unwanted changes to the ensemble of monuments to a minimum. Conservation work must encompasses both small details and the big picture.

Over the past 20 years, the conservation and restoration work done in Naga has shown the importance of a good working relationship between the different disciplines involved – archaeology, architectural history, surveying, restoration and material sciences. The continuity of the work and the constant evolution of the methods used has set the standard in this field, providing an example now followed by other archaeological excavations in the Sudan. The excavation has been continuously accompanied by restorators since the end of the 1990s.

Financing

The Naga Project is financed entirely by third-party funds.

Current:

Previous:

- Qatar Sudan Archaeological Project (2014 – 2019)

- DFG – German Research Association (Sponsoring from 1995 – 2009)

- Verein zur Förderung des Ägyptischen Museums Berlin e.V. / Friends of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin

- Westdeutsche Gipswerke Gebrüder Knauf, Iphofen

Sponsoring

Are you interested in supporting our project? We would be delighted to receive your donation.

either directly to the Egyptian Museum under the following bank account

Staatsoberkasse Bayern in Landshut

Bayerische Landesbank München

BIC: BYLADEMM

IBADN: DE75 7005 0000 0001 1903 15

Please specify in the intended use:

“2525.2400.0040, Spende Naga-Projekt SMÄK”

or via the friends’ association of the museum under the following bank account

Freundeskreis des Ägyptischen Museums e.V.

Deutsche Kreditbank

BIC: BYLADEM1001

IBAN: DE 79 1203 0000 1004 3765 78

Please specify in the intended use:

“Spende Naga-Projekt SMÄK”