School

This page offers an overview of the Ancient Sudan’s rich and varied history for schools or other interested visitors. All the information is also available to download.

Teacher handout Nubia and Sudan | دليل الأساتذة الارشادي للنوبة والسودان

The Rediscovery of Nubia

European authors contemporary to Ancient Nubia were well aware of its existence – the Greeks called the entire area south of Egypt, regardless of culture, “Ethiopia” (“the land of those burned by the sun”). Herodotus, Diodorus, Strabo, Cassius Dio and Pliny all described it, and it even gets a mention in the Bible:”… and lo, a man from the land of the Moors, a Chamberlain and high official of the Candace, Queen of the Ethiopians [Meroë], who was in charge of her Treasury, had come to Jerusalem to worship.” [Acts 8:27]. Later, numerous Church authors reported on the Christianisation of the Sudan in the 6th century; of particular importance are the works of John of Ephesus.

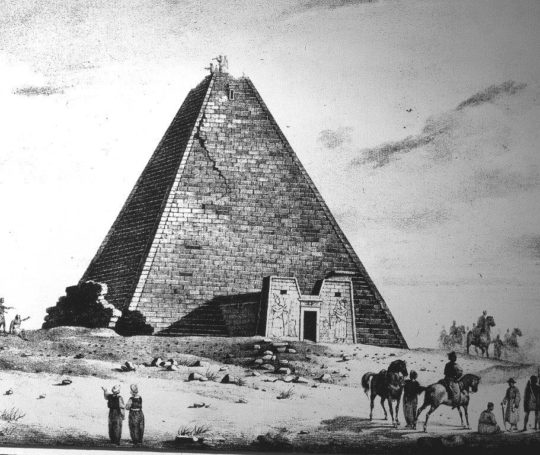

In more modern times, James Bruce was the first to recognise Ancient Meroë in the pyramid field of Begrawiyah in 1722. When Mohammed Ali sent his troops into the Sudan in pursuit of the last of the Mameluks in 1821 – and conquered the Funji Sultanate of Sennar in the process – European adventurers among the soldiers were curious about the ruins and wrote the first reports about them, sparking more interest in Ancient Nubia.

The most prominent of these pioneers in archaeology is French naturalist Frédéric Cailliaud whose work, published in 1826, remains indispensable today, as it documents both in writing and sketches many sites that are now destroyed. Linant de Bellefonds, Waddington, Hanbury and Hoskins as well as Lord von Prudhoe all travelled the Sudan at the same period and published their experiences. Giuseppe Ferlini, a military doctor from Bologna, came to Meroë in 1834 where he discovered the treasure of the Meroitic queen Amanishakheto.

The high point of 19th-century archaeological research into the Sudan was the Prussian expedition under Richard Lepsius 1842-1845, which documented practically all the monuments visible at the time, all the way down to Sennar. Then comes a gap in archaeological interest in the Sudan in the second half of the 19th century. Not until after the Maadi Insurrection (1881-1898) which ended with the conquest of the land by anglo-egyptian troops did archaeologists – at first, mostly British ones – come once again to Nubia.

Frédéric Cailliaud (1822): The North Cemetery of Meroe

“The Nubian Campaign”

Since the beginning of the 20th century, research into Ancient Nubia has gained momentum – though not entirely of its own accord. Three large-scale international campaigns were instigated as a reaction to the erection – or rather, raising – of a dam at the First Cataract near Aswan, in order to document and, if possible, save the monuments and archaeological sites threatened by the rising waters of the dam.

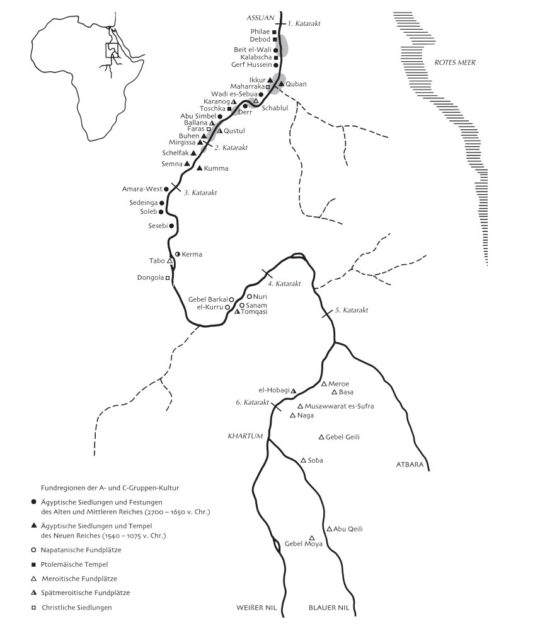

The first dam, erected in 1902, had already been raised in 1912. In a first campaign under the direction of G. Reisner and C.-M. Firth, more than 40 cemeteries were excavated between Aswan and Wadi es-Sebua from 1907-1911, as well as some of the forts such as Ikkur and Quban. On the basis of these excavations, Reisner elaborated a typology and chronology for the Ancient Sudan which, in its broad strokes at least, is still used today.

The second raising of the dam, completed in 1933, would flood the area south of the Wadi es-Sebua down to Adindan, leading to a second Nubian Campaign under the direction of W.B. Emery and L.-P- Kirwan. Its greatest feat was the discovery of royal tombs from a Late Meroitic culture (X-Group) in Ballana and Qustul.

© SMÄK

© SMÄKIn 1959, Egypt decided to build the Aswan High Dam, which would flood the entire area between Aswan and Dal south of the Second Cataract. Answering an appeal from UNESCO to help Egypt and the Sudan in saving Nubia’s rich cultural heritage, between 1960 and 1967 more than 30 archaeological teams were actively working to save and document as many sites as possible before they disappeared under the waters. The most spectacular result of that call to arms was the relocation of the rock-cut temple of Ramses II in Abu Simbel.

Other temple complexes were also relocated at a higher level, such as the temples of Wadi es-Sebua, Beit el-Wali or Kalabsha. Others were gifted by Egypt to the countries who took part in the campaign as thanks for their role in preserving Nubia’s heritage. This is how the Temple of Dendur came to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Temple of Debod to Madrid, the rock-cut chapel of Ellesiyah to Turin, the Temple of Taffeh to Leiden and the Kalabsha Gate to Berlin. Other buildings, such as the majestic fortresses of the Middle Kingdom, have disappeared beneath the waters.

Systematic archaeological surveys took place and monuments were displaced in the Sudan as well, among them the temples of Buhen, Semna and Kumna. Under the direction of Berlin architect and architecture historian Friedrich Hinkel, they were dismantled and carted to Khartoum in order to be rebuilt in the archaeological open-air park of a museum still under construction at the time. In 1972, the National Museum of Khartoum opened its doors to the public. It is currently undergoing renovation and enlargement.

From 2004 to 2009, a new dam, the Merowe dam, was built near the Fourth Cataract. Archaeological missions from the Sudan, Poland, Germany, France, the UK and Italy have documented numerous archaeological sites dating from the Neolithic to the Islamic Period in the area of the 180 km-long reservoir lake of 180km.

Egypt is in Africa

The history of the cultures of the Ancient Sudan forces us to reconsider the traditionally-held views on the history of the Nile Valley, which historically focuses mostly on Ancient Egypt. Nubia, the area between the First Cataract in the North and Khartoum in the South, encompassing southern Egypt and northern Sudan, has always stood in the shadow of the Pharaonic Kingdom, which had in fact conquered Nubia several times. It was the gold deposits in the Nubian desert that made the land so attractive to its powerful northern neighbour.

The Egyptians generally called the land “Kush” and – in the official records at least – tended to look down on their southern neighbours. One important reason for this was the fact that the Nubian cultures did not have a writing system. Despite knowing about the Egyptian writing system, it wasn’t until the 2nd century BC that they eventually invented their own script. There seems to have been no need for one before – they simply used Egyptian hieroglyphs if they needed to communicate in written form.

The fate of being considered second-rate has affected Nubia again much more recently: Egyptology, traditionally a philologically-centred subject, tended to parrot the views of the Ancient Egyptians, according only a cursory interest to the cultures of the Ancient Sudan. The individuality of their culture was considered minimal or entirely overlooked; even the influences of Black culture on Egypt itself has barely been the object of scientific research.

And yet, Prehistoric Nubian cultures were at least five milennia ahead of the Egyptian ones; especially in the early phases of Egyptian culture, African influences abound: rituals, elements of royal ceremonial attire, attendant burials, the power accorded to women of power, the appearance and attributes of certain deities, were all elements taken from or influenced by the South. The development of ceramics started in northern Sudan around 10.000 BP.

Only recently have scholars begun to use ethnological data to help analyse visual and archaeological finds from Ancient Egypt. This scientific dialogue needs to continue and expand; ethnological field research needs to intensify, not just in other African countries, but also in the Sudan. An important step in the rehabilitation of ancient Nubia is the declaration of the monuments in the area of the Gebel Barkal and of the archaeological zone of Meroe with Meroe, Musawwarat and Naga as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Ancient Nubia was at the centre of an intense north-south dialogue – a stepping-stone between East Africa – the Cradle of Humanity – and the Mediterranean World.

Historical Overview

Nubia and Sudan

Neolithic cultures — 6000-3500 BC

—

A-Group culture in lower Nubia — 3500-2800 BC

—

—

C-Group culture in lower Nubia — 2300-1600 BC

The Kingdom of Kerma in upper Nubia — 2500-1500 BC

—

—

—

Nubia under egyptian rule — 1550-1070 BC

—

The Kushite Dynasty —1000-650 BC

—

The Kingdom of Napata — 650-310 BC

—

The Kingdom of Meroe — 300 BC – 320 AD

—

Late meroitic Kingdoms — 350-600 AD

—

Christianization — 540-580 AD

Islamization — beginning in 642 AD

Egypt

—

4300-3000 BC — prehistoric cultures

—

3000-2700 BC — Early Dynastic

2700-2170 BC — Old Kingdom

—

—

2170-2040 BC — 1st Intermediate Period

2040-1780 BC — Middle Kingdom

1780-1550 BC — 2nd Intermediate Period

1550-1070 BC — New Kingdom

1070-750 BC — 3rd Intermediate Period

—

750-656 BC — The Kushite Dynasty in Egypt

650-310 BC —Late Period

332-30 BC — Ptolemaic Period

—

30 BC – 395 AD — Roman Period

—

395-600 AD Byzantine Period

—

beginning 642 AD — Islamization

Neolithic cultures

Recent excavations have shown that the prehistorical cultures of the Sudan are much older than those of Egypt; high-quality pottery was being made in the Sudan several millennia before Egyptian ceramic production began. However, until recently, examples of this high-quality ware, used as funerary offerings, were not well-known among scholars. In the area of pottery, Nubia would remain superior to Egypt throughout its ancient history.

At the beginning, we have the Khartoum Neolithic culture, often named after its main site Shaheynab, south of the Sixth Cataract. Finds reach back to the 6th millennium BC. Other important sites are Early Neolithic Kadero (5th millennium BC) at the northern edge of the city of Khartoum, joined in the first half of the 4th millennium BC by el-Kadada in the area around Shendi, about 180 km down the Nile. In parallel, research has concentrated in the past few years on Kadruka below the Third Cataract. In 2006, in the area just around Kerma, potsherds were found at el-Barga that have been dated to the Late Palaeolithic Period – the 10th to 9th millennium BC.

Most finds come from tombs in extensive necropolises. The way the tombs are arranged often gives insight into the social structure of these Neolithic cultures. For the first time, tombs are round – this would remain a characteristic element of Nubian funerary culture for the next two thousand years. Pottery, weapons and tools have all survived, as have early examples of sculpture, already quite advanced. The figures are all female with exaggerated secondary sexual features. A corpus of recently-discovered idols, now in the National Museum of Khartoum, is the largest find of statuettes to date.

Pottery, weapons and tools have all survived, as have early examples of sculpture, already quite advanced. The figures are all female with exaggerated secondary sexual features. A corpus of recently-discovered idols, now in the National Museum of Khartoum, is the largest find of statuettes to date.

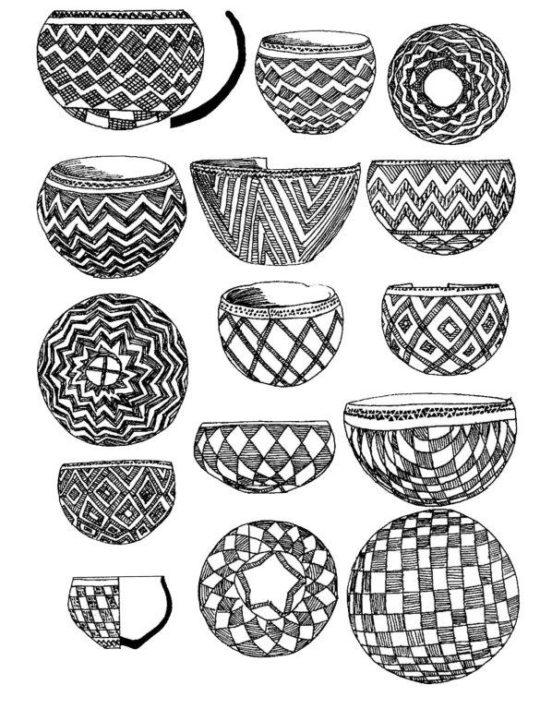

Nubian Pottery

One highlight of Nubian cultures from the Neolithic up until the Late Meroitic Period is the high quality of the pottery. Its uniqueness lies not only in the shapes of the pots, but also in their surface polishing and decoration, though there are parallels to wares from other African cultures. In profile, the vessels exhibit a tension that remains one of the main characteristics of Nubian pottery, a style that endured for over five millennia, from the Neolithic through the A-Group, Kerma and finally into the Late Meroitic Period.

As early as the late 5th/early 4th millennium, finds from the Neolithic Period show a technological and artistic standard that has no parallel in Egypt. The excellent quality of Neolithic pottery and the beauty of its decoration survives in the pottery of the A and C Group cultures. In Egypt, where sculpture, reliefs and painting quickly achieved a masterful quality, pottery was mostly for daily use and remained unremarkable. In Nubia, however, pottery became the preferred means of artistic expression.

In Kerma, pottery artists achieved a rare, difficulty surpassed level of perfection. In their shape and surface treatment, the tulip vases and spouted pots achieved a visual balance that raises them almost to the rank of abstract sculptures. The quality of pottery production only went down during periods of Egyptian rule and in the Napatean Period, which includes a phase in which the Kushites ruled Egypt.

However, in the Meroitic Period, without much of an adjustment period, pottery once more achieved a high standard. It is possible to identify production centres and workshops, sometimes even the style of individual painters. Though the decoration repertoire uses Egyptian symbols and floral ornaments as well as some Hellenistic motifs, a highly-original autonomous pictorial language was also elaborated that makes it easy to identify Meroitic pottery. The post-Meroitic X-Group culture developed its own formal language, but used a lot of motifs from Late Antiquity such as grape vines, vines and garlands and is, in its decoration, difficult to set apart from Early Christian wares.

A-Group Culture

The names for the Nubian cultures currently in use hark back to American Egyptologist George Reisner, who excavated many sites along the Nile at the beginning of the 20th century. A-Group sites are concentrated in the area between the First and Second Cataracts. Their historical development is divided into three stages: Early (3700-3250 BC), Classic (3250-3150 BC) and Late A-Group (3150-2800 BC).

The A-Group culture at first parallels the prehistorical Naqada cultures of Egypt, with whom they engaged in a lively trade. This is evident from finds of typical Egyptian pottery – such as cylindrical vases with a painted net pattern – brought into A-Group land as imports and then deposited in Nubian tombs as funerary offerings. The A-Group’s territory lay along a trade route channelling wares from central Africa and the Red Sea (such as ivory, ebony, incense, skins and, for the first time, gold) into Egypt and beyond.

As Egypt increasingly turned its attention southwards over the course of the Early Dynastic Period, the A-Group seems to have slowly lost control over this trade, as Egyptian goods they would have received in exchange such as pottery, weapons and tools are missing from tombs of that period. The slow depopulation of Nubia starting around 2800 BC may have been a result of climatic changes; Reisner’s B-Group culture, dating to that period, has since been recognised as an impoverished A-Group rather than a separate culture.

© SMÄK

© SMÄKThe Late Neolithic tradition of round graves covered with a tumulus (funerary mound made of rubble) was continued; finds of post holes in settlement sites show that houses were round as well. The typical pottery of the A-Group culture is a deep bowl with decoration that often imitates basketry. Incised decoration is usually limited to a thin band along the edge of the vessel. The pots are frequently blackened on the inside during a second firing.

Egypt and Nubia in the Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom

The trade relations between Prehistorical Egypt and the A-Group are well documented. The beginning of the Early Dynastic Period (ca. 3000 BC) also heralded the first of the military clashes that would lead to the Egyptian occupation of Nubia under the main epochs of Pharaonic Egypt – the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms. During each of the “Intermediate Periods” between them, Egypt retreated from Nubia, allowing indigenous Nubian culture to flourish.

© SMÄK

© SMÄKThe first written document to mention military actions against Nubia is an ivory label of King Aha of the 1st Dynasty where he rejoices over a victory over “Ta-Seti” (Nubia). Under his successor Djer, Egyptian troops reached the Second Cataract, a fact immortalised on a rock-cut inscription in the Gebel Sheikh Suliman. Further military activity is reported for the 2nd Dynasty as well. Though the Early Dynastic Period does not seem to have seen a systematic colonisation of Nubia, the A-Group slowly lost control of trade with central Africa.

The Old Kingdom (2700-2250 BC) marks the beginning of the great expeditions to the South. An Egyptian outpost was founded near the Wadi Halfa. On the Palermo Stone, the Annals from the reign of Snofru from the 4th Dynasty mention a military expedition that captured 7,000 prisoners and huge herds of livestock. Another destination for Egyptian expeditions were the stone quarries of Toshka, where diorite was quarried during the reign of Kheops.

In the 6th Dynasty, General Uni led an expedition into Nubia in order to bring back a stone sarcophagus for King Merenre from the quarries there. To help transport it back to Egypt, a channel was dug through the First Cataract. In a long inscription in his tomb, the Nomarch Harkhuf describes several expeditions into the land of Yam (probably the area around the Dongola Basin) from which he brought luxury items back to Egypt on the backs of 300 donkeys – including a Pygmy for the court of his King, Pepi II.

In Egyptian art, a “Nubian” style, characterised by stockier proportions and a more robust physique, is recognisable in Upper Egyptian artefacts as early as the Old Kingdom. This would become typical for statues and reliefs created in Nubia, as well as the depiction of Nubians in Egyptian art.

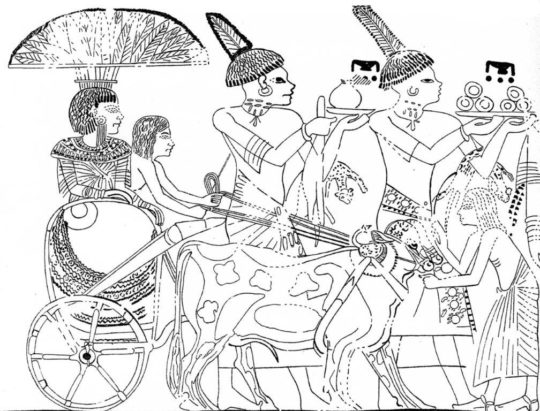

The image of Nubians in Egypt

The Egyptian view of the world revolved around the concept of “Maat”: justice and world order. To reach and uphold the state of Maat was the main responsibility of the Egyptian king. This included the destruction of chaos, symbolised by foreign enemies. While the position of northern enemies could be cast differently (Syrian, Mitanni, Hittites), the southern enemy was always the same: the Nubian.

Nubians not only appeared in the traditional motif of the “Destruction of Enemies”; the subjugation theme also appeared on various smaller objects showing bound Nubians: on figurative handles, sandals, vessels or wall or floor tiles of faience used to decorate the throne room of royal palaces. One common trope was the depiction of a bound Nubian in the shape of a “city ring”: the lower body was formed by the oval of a wall fortification, in which the name of a subjugated city or region was inscribed.

© SMÄK

© SMÄK

Many texts also paint a disparaging picture of Nubians, such as the common description of Nubian chieftains as the “Wretched One of Kush”. In the Semna stela, a border marker of the Egyptian king Sesostris III, Nubians are described thus: “They are not people who have earned respect, they are piteous and cowards.” This description corresponds to certain caricaturising depictions in art over-emphasizing Black features.

Parallel to these depictions in line with the royal dogma, there is another image of Nubians, more realistic, generally mirroring their esteem within Egyptian society. This is especially true for female servants, nurses and musicians from Nubia who were often cherished members of high-society households and were often depicted on cosmetic objects such as mirrors and makeup spoons. Marriages between Egyptians and Nubians were common; Nubian princesses are often documented among the Pharaoh’s wives. Nubians served as elite troops in the Egyptian army.

Southern Nubia and other African regions were designated as “ta-netjer”, the Divine Lands. This was considered the origin of Bes, protective deity of mother and child. Animals from the south, such as dryas monkeys, were often held as pets.

C-Group Culture

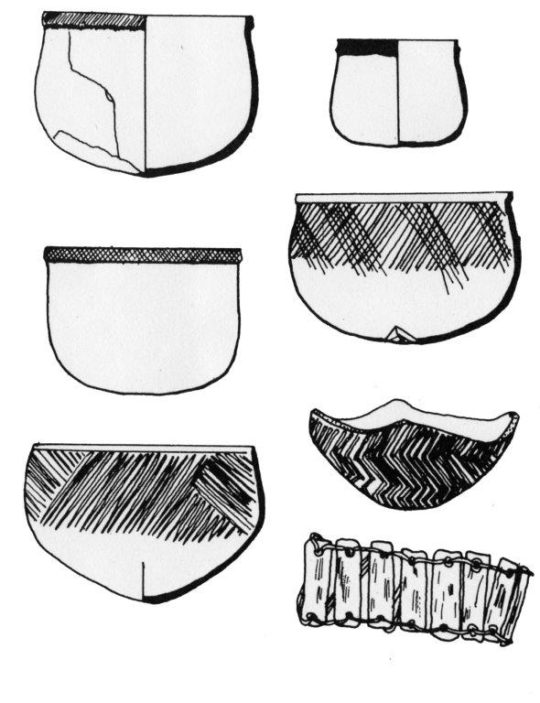

The A-Group villages between the First and Second Cataracts were later settled by the C-Group. This culture lasted from 2300 to 1500 BC and can be divided into several periods: it begins around 2300 BC with Egypt’s slow retreat from Nubia (with the exception of a few isolated expeditions) in the Late Old Kingdom to deal with internal political problems. This early phase lasted parallel to the Egyptian Middle Kingdom until 1900 BC; during this time, the C-Group territory in Lower Nubia was mostly under Egyptian administration.

The peak of C-Group culture was during its second phase, from 1900 to 1600 BC. The retreat of the Egyptian presence from Nubia after the end of the Middle Kingdom led to an increase in C-Group settlements. The tumulus tombs often had a small offering chapel on the eastern side. The deceased was buried lying on a bed and small clay statuettes of people and their livestock – cattle, sheep and goats – can be found among the grave goods.

Typical examples of the high-quality C-Group pottery include small, globular bowls and deep dishes with incised decoration. Zig-zag and diamond patterns are highlighted in white paste; basketry motifs appear once more. In luxury goods, the paste can be of several different colours. Pottery of a somewhat coarser ware sometimes includes figurative decoration, also incised.

© SMÄK

© SMÄKPan-Grave Culture

© SMÄK

© SMÄKContemporary to the C-Group, in the Eastern Desert, the Pan-Grave culture (named after their round, shallow graves) flourished. They were probably nomads. This is suggested, among other things, by the simplicity of their graves, but also their simpler, coarser pottery compared with the C-Group. Although the types of vessel are very similar, as is the incised decoration, they are not so finely executed. One typical shape is a bowl with a zig-zag rim, which may have been an imitation of a type of leather bag.

A characteristic element of Pan-Grave grave goods are the horns (bucrania) from goats and sheep (more rarely cattle), another clue to the nomadic, herding lifestyle of the Medjay (as the Egyptians called them). These horns are usually painted in ochre colours, in some rare cases with ornamental or even figurative decoration. Another characteristic of Pan-Grave culture is jewellery such as necklaces or bracelets made of thin strips of mother-of-pearl.

Egypt and Nubia in the Middle Kingdom

Although Egypt’s influence over Nubia was reduced during the First Intermediate Period, contact was never completely broken off: in his tomb in Mo’alla, a Nomarch of Upper Egypt, Ankhtifi, mentions grain deliveries to Wawat (a region in Nubia) in order to prevent a famine. Not long after 2040 BC and the re-unification under Mentuhotep II (who had a Nubian among his six royal wives), reports of military campaigns against the South appear once more in the records at the end of the 11th Dynasty.

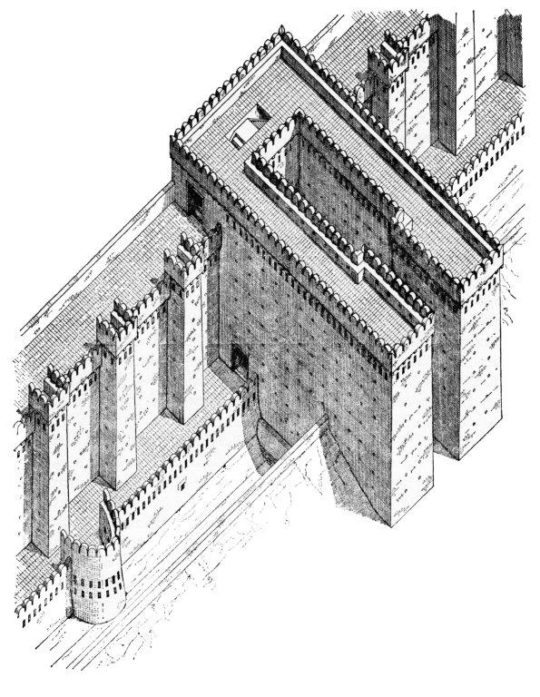

In the 12th Dynasty (1994-1781 BC), the first phase of what would become a systematic colonisation of Nubia began. The founder of the dynasty, Amenemhat I, subjugated the area around Lower Nubia towards the end of his reign (ca. 1975 BC); his successor, Sesostris I, was already leading campaigns beyond the Second Cataract, definitely as far as Sai and possibly beyond. To protect the trade caravans and quarry expeditions as well as the entrance to the gold mines in the Wadi Allaki in the Eastern Desert, a whole chain of fortresses were erected between the First and Second Cataract – imposing fortifications with mudbrick battlements and fire-steps, deep moats and bulwarks up to 15 m high. Opponents were members of the Kingdom of Kerma south of the Second Cataract as well as groups of Bedja in the Eastern desert.

In these fortresses, Egyptian occupation troops lived together with their families, as finds from the adjacent necropolises show. Small temples within the forts were dedicated to Egyptian gods. There was a lot of contact with the contemporary Nubian C-Group culture, which mostly retained its cultural identity under Egyptian occupation.

© SMÄK

© SMÄKThe southern border of the Kingdom of Egypt was at the double fortress of Semna/Kumna on the Second Cataract. It was defined by Sesostris III in a historical inscription on a border stela. Under the New Kingdom, this ruler would be deified in Nubia as local god. Magical practices – bound figures of clay (more seldom of stone) or pots with execration formulae – were meant to add additional protection against opposing forces.

Starting around 1750 BC, the weakening of the Egyptian state over the course of the 13th Dynasty, led to the abandonment of the fortresses. They were occupied by the Kingdom of Kerma over the course of the Second Intermediate Period. At the same time, groups of Bedja nomads slowly became sedentary and settled along the Nile valley.

The Kingdom of Kerma

The imposing Egyptian fortresses built on the Second Cataract during the Middle Kingdom were a rampart against a military power that had arisen during the First Intermediate Period: Kerma, the first of the Ancient Sudanese Kingdoms. Its influence stretched from the Second Cataract up to the Fourth Cataract, with its capital near the Third Cataract. In the Second Intermediate Period, Lower Nubia was also part of its territory for a time. Precursors to this culture can be documented as early as 3000 BC (Pre-Kerma culture).

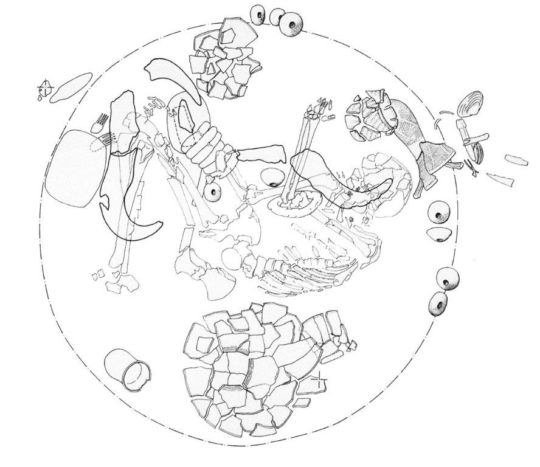

The huge tumulus tombs of the Kerma kings (up to 70m or over 220 ft in diameter) have yielded rich grave goods that underline the individuality of this culture. Among them, figurative applications made of paper-thin mica. According to Nubian tradition, the kings were buried on wooden beds. The tradition of servant burials – with up to 400 people accompanying their ruler in death – can occasionally be observed in C-Group cemeteries as well. A large number of oxhorns (bucrania) ringing some of the tumuli suggest that owning cattle was a sign of wealth.

The Deffufas, were monumental cultic buildings: massive blocks of mudbrick with slim passages and columned rooms inside, their walls decorated with paintings. Large-format wall inlays of faience illustrate the high standard of Kerma technology.

However, the most impressive aspect of Kerma culture is its pottery: with its elegant shapes and eggshell-thin walls, the vessels of the Classical Period (1750-1500 BC) are among the best ever produced along the Nile Valley. Equally impressive are the figurative vases in the shape of animals, some of them with relief decoration. Painted vessels in the shape of round huts depict the main architectural features of Kerma houses.

© SMÄK

© SMÄKNumerous objects of obvious Egyptian provenance, especially statues, at first caused the first excavator George Reisner to identify the Kerma culture as an outpost of the Pharaonic Kingdom. Apparently, the court of Kerma had a certain fondness for Egyptiaca and Egyptian objects were therefore imported into Kerma as trade goods, diplomatic gifts or even as spoils of war. Kerma controlled the Nile Valley down to the First Cataract; military campaigns even reached Upper Egypt.

Egypt and Nubia in the New Kingdom

The Kingdom of Kerma is the only Nubian culture to have been completely erased as a political power through Egyptian military action – without lossing its ethnic identity. In the Second Intermediate Period, the Hyksos foreign rulers residing in the Eastern Delta had attempted to forge an alliance with Kerma. This was discovered by the Theban king Kamose who managed to foil the plan. Once the Hyksos had been cast out of the North, the re-conquest of the South began with the start of the 18th Dynasty (ca. 1500 BC).

© SMÄK

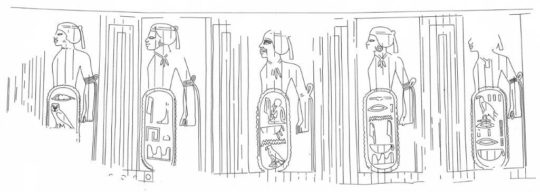

© SMÄKThe Middle Kingdom fortresses in Lower Nubia were restored and expanded; their mudbrick temples rebuilt in stone. Soon, Egyptians lived there in greater numbers – and in anything but poverty, as evidenced by luxurious grave goods such as weapons and tools. The conquered region was administered by a high-ranking Egyptian official, the “King’s Son of Kush” (or “Viceroy of Kush”) and completely integrated into the Egyptian administration and economy. For the period up to the end of the 18th Dynasty around 1320 BC, each of the sub-districts or ethnicities retained their local chieftains, who were mostly responsible for organising tribute. Children of these Nubian chiefs were fostered at the Egyptian court in order to model them into loyal subjects. Egyptian temples were built south of the Second Cataract at Amara, Sedeinga, Soleb, Sesesebi and Gebel Barkal; but at the former capital of Kerma, sanctuaries for local gods continued besides Egyptian temples.

The Kushite Dynasty – Egypt Under Nubian Rule

When Egypt was forced to retreat from Nubia at the end of the New Kingdom (ca. 1100 BC), the resulting power vacuum in the region gave rise to a new Nubian culture, which would soon expand northwards. The Kingdom of Napata, with its capital at the Gebel Barkal (the “Holy Mountain”) was the first and only Nubian culture to have conquered Egypt and ruled it for just over a century (750-656 BC). This period is designated in Egypt as the 25th Dynasty – the Kushites, as they were called, ruled as Black Pharaohs. In 725 BC, King Piye conquered Egypt down to the Delta.

The God’s Wives of Amun played an important role in the transfer of power. The God’s Wife was a priestly rank reserved for women which, over the course of the Third Intermediate Period, had acquired a rising political function as well. The title was passed on through adoption; the Kushite king Piye had ensured that his sister Amenirdis was adopted by the sitting Egyptian God’s Wife of Amun. The quality of the statuary of these Nubian royal princesses demonstrates the priestess’s secular power; they basically ruled Egypt as regents for the Kushite kings.

Through this closer contact with Egyptian culture, some aspects of the Kushite’s Nubian culture became Egyptianised, especially in the areas of afterlife beliefs and tomb architecture: the native round tumulus tombs gave way to pyramids for the ruling family. Extensive pyramid fields sprouted first in el-Kurru, then in Nuri. However, the shape of these funerary monuments is based not on the classical pyramids of the Old Kingdom, but on the much smaller pyramids that topped the entrance to the tombs of Egyptian officials of the New Kingdom. The decoration of the burial chambers borrows from motifs and texts of the Egyptian Book of the Dead; among the grave goods are quantities of ushebtis (small servant statuettes). Only in the use of beds instead of coffins for the body does the Nubian funerary tradition live on.

The new (foreign) rulers of Egypt injected new life into its art and culture. In keeping with the Pharaonic tradition, the Kushites engaged in a lively building activity in all the most important temples. Similarly, they took inspiration from royal names of the Old Kingdom for their royal titulary. But their most important contribution was in giving Egyptian art, which had become stiff and schematic, new inspiration and impulses. The stockier proportions and different physiognomy of the Kushites were translated into new proportions for an ideal athletic body and influenced the features of impressive individualistic portraits.

The Kingdom of Napata

The intervention of Kushite rulers in the resistance of the Syrian-Palestinian states against the Neo-Assyrian Empire twice led to Assyrian invasions of Egypt (671 and 666 BC). The 26th Dynasty, originating in Sais, eventually got the upper hand, forcing Tanutamani, the last of the Kushite pharaohs, to retreat from Egypt. Lower Nubia was once more claimed by Egypt, and in the year 591 BC a campaign under the Egyptian king Psamtik II even made it into Upper Nubia, possibly all the way to Napata. A campaign by the Persian king Cambyses, however, failed.

With the loss of Egypt leading to a retreat back into its core territories, the Kingdom of Napata entered a phase of relative isolation, apparent among other things later in the 4th century BC stela of Nastasen, with its error-ridden hieroglyphs and poor knowledge of the Egyptian language (which had been used for official monuments since the Kushite Period.)

The individuality of the Kushite style of statuary was further developed and began to drift away from its Egyptian model in favour of its African component: proportions became stockier, features became more African with fuller lips, wider noses and smaller foreheads. Otherwise, artistic production was still very much in the Egyptian tradition. No other Nubian culture achieved the quality and quantity of Kushite-Napatan statuary. It was probably no coincidence that pottery production declined in quality during this period.

At the Gebel Barkal, a huge temple city arose, comparable to Karnak in Egypt. Inscriptions on the temple walls contained reports on the kings’ ascension to the throne, endowments for the gods and military campaigns. They document the increasing influence of the state god Amun of Napata through oracular decrees.

This included the choice of the next king, though the military was at least nominally included in the process. Though a king’s sons were the first choice for his succession, sisters of the king frequently played an important role in kingmaking in their roles as priestesses. The importance of female members of the royal family continued on during the Meroitic Kingdom.

Stela of Nastasen

“Year 8, Month 1 of the Flood Season, day 9 under the Horus, the Strong Bull beloved of the Ennead, He Who Has Appeared in Napata, the Lord of the Crowns, the Son of Re, Nastasen, the bull who tramples his enemies under his soles, the great mauling lion, the fortifier of all lands, the son of Amun with a strong arm who expands all lands, the son of the gods. […] As I was in Meroë, my father, Amun of Napata, called to me: “Come!” I set forth… [to Napata]. I overheard travellers saying: “He is in the capital of all lands.” I set forth and soon reached Teka, the Great Lion, the garden from which the Kings Piye and Alara sprouted. Then all the people came out to me from the Temple of Amun in Napata and the cities, all of them high-ranking nobles. They spoke with me and said: “Amun of Napata, your great father, has put the dominion of Nubia at your feet.” Everone asked: “When did he land?” […] I mounted large horses and reached the great temple. All of the nobles and priests of Amun threw themselves down before me. Every mouth praised me. I told Amun of Napata, my father, everything that weighed on my heart. He listened to my speech. My father, Amun of Napata, gave me the kingship of Nubia, the crown of King Harsiotef and the power of Kings Piye and Alara.

[…] I held my palaver with Re and spoke the following speech to Amun of Napata: “You have called me out of Meroë and I have come to you. You have put the dominion of Nubia at my feet. It is not men who have made me king.” […] Everybody said: “He does everything well. Amun of Napata has given him dominion over Nubia. The son of Re, Nastasen, has risen and now sits in the shade on the golden throne. He will be King and sit and live in Meroë.” […] And something else again: I sent the army go forth against the enemy from Makhandakenenet. They fought with him, a great massacre. I captured their chief Iyahek. I captured all their women, all their livestock, quantities of gold: 209,659 head of cattle, 503,349 small livestock, 2,236 women. […] And something else again: I send the army forth against the enemies from Raber and Iakerkereh. I made a great massacre. I captured their chieftain Rabeheden, all of his possessions in gold, innumerous: 203,216 head of cattle, 603,107 head of small livestock, all his women, everything people use to feed themselves.”

Stela from the Gebel Barkal, Napatan, ca. 330 BC

The Kingdom of Meroe

Toward 300 BC, a change seems to have occurred in the royal house of the Kingdom of Napata; according to Greek sources, King Ergamenes freed himself from the influence of the priests of Amun. He moved the royal necropolis from Nuri to Meroë, where other members of the ruling family had previously been interred. Next to temples for Egyptian gods such as the Temples of Amun of Meroë and Naga, he and his successors also erected sanctuaries for local deities such as lion-headed Apedemak in Musawwarat es-Sufra and Naga.

The Kingdom of Meroë was at first contemporary to the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt after its conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BC, then later became a liminal culture of the Roman Empire. Around 275 BC, Ptolemy II invaded Lower Nubia and sent exploratory and animal-catching expeditions further south. An insurrection in Upper Egypt (204-185 BC) returned Lower Nubia to the Kingdom of Meroë. This established strong relations to the island of Philae, which, as the cult centre of the goddess Isis, was of great importance to both Egypt and Meroë. Seven years after Egypt became a Roman province under Augustus, Roman troops invaded Meroë in 24 BC, making it all the way to Napata. However, a truce was brokered to Meroë’s advantage, with Lower Nubia divided between Meroë and Rome as a puffer zone.

The history of Meroitic art has yet to be written; as the finds are still too few and far between. Large animal statues depicting aspects of gods – rams, lions, frogs – seem to play an important role. Statues of royals and gods in human shape are known from only a few examples. Unusual for their stylistic variety is the group of so-called Ba statues – funerary statues of non-royal people – which show stylistic similarities to the contemporary Nok culture of Nigeria, some 2500 km away.

The diversity of architecture in Naga showcases Meroe’s identity as a bridge between Africa and the Mediterranean world, integrating African, Egyptian and Hellenistic influences.

Meroitic pottery is also a good example of the multiculturalism of Meroitic art – a bridge between Africa and the Mediterranean world. Hellenistic vase shapes and decorations such as the “Barbotine” ware, painted Egyptian motifs in the shape of hieroglyphs (Ankhs) and typical African pottery types such as large, big-bellied jars with small opening for storing and keeping water cool all appeared side by side.

Meroitic Writing

For thousands of years, the Nubian cultures did not see the need to develop writing systems for their various languages; they remained illiterate. Yet, through their near-constant contact with Egypt, it was obvious that they were aware of the many ways writing could be of use; and in some cases they even used the Egyptian script and language for their own monuments. But it isn’t until the 2nd century BC that written monuments appear in the Kingdom of Meroë documenting the indigenous language with its very own writing.

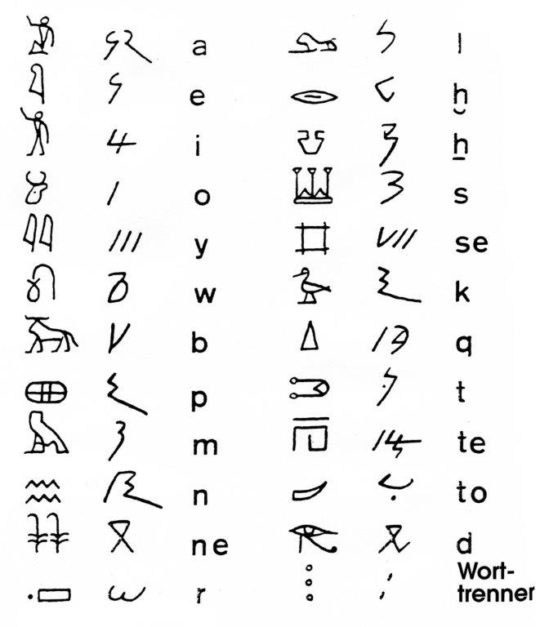

© SMÄK

© SMÄKAt first, the symbols were taken from a cursive writing derived from an Egyptian administrative script called Demotic. A rarely-used hieroglyphic version was added later. The writing system had 15 symbols for consonants, four symbols for common syllables and three for vowels. They used word separators, which were unknown in Egyptian writing. The numbers also derived from the Egyptian script.

The structure of the Meroitic language classifies it among the family of agglutinative languages. It probably belonged to the group of Nilotic-Saharan languages (such as Dinka and Masai) which today encompasses the eastern Sudan and the upper Nile regions.

The Meroitic script was deciphered already in the early 20th century, but the language is still not completely understood: longer historical inscriptions, of which only a few have survived, cannot yet be translated in their entirety. Because of their formulaic nature, the short texts on stelae and offering tables can usually be understood.

The Treasure of Amanishakheto

The kings and queens of the Kingdom of Meroë (ca. 300 BC-350 AD) followed the Ancient Egyptian tradition of having themselves buried in pyramids. The Meroitic necropolis of Begrawia lies not far from the Residence of Meroë. At the beginning of the 19th century, these pyramids were still well-preserved, though for the most part plundered in Antiquity. One exception was pyramid N6, that of Queen Amanishakheto.

The Italian doctor Giuseppe Ferlini came to the Sudan with Mohammed Alis troops and had it dismantled, together with several other pyramids, in search of treasure. He quite literally struck gold: a clearly untouched gold treasure which Ferlini soon brought out of the country. In an Italian catalogue published in 1837 in Bologna, then in a French version published in Rome one year later, he presented the treasure to the public and searched for buyers.

In 1839, part of the find was bought by Ludwig I for the royal Bavarian art collections; the other half remained unsellable for a time, in part because of the unusual style of the jewellery, which raised doubts as to the authenticity of the find. This doubt was not lifted until a decade later when Richard Lepsius, who had already suggested that the treasure be acquired for the Egyptian Museum of Berlin, came to Meroë during his Egyptian-Sudan expedition and saw original Meroitic artwork. On his recommendation, the rest of the treasure was acquired for Berlin in 1844.

The circumstances of the find are unclear. In his report, Ferlini gives the impression that the treasure was found in a chamber high up inside the pyramid. Yet none of the Napatan or Meroitic pyramids provide a parallel for this. Additionally, structural considerations speak against a chamber within the masonry. It seems likely that the treasure of Amanishakheto came from the burial chamber under her pyramid instead, which Ferlini’s workers would have broken into from above when dismantling the pyramid. A large part of it was wrapped in a cloth and placed inside a bronze vessel; other piecess were found on the floor of the chamber.

The artisanal quality of the pieces is not equal to that of Hellenistic goldsmiths from the Mediterranean. The importance of this find lies instead in the combination of Egyptian, Meroitic and even some Hellenistic elements to form a unique style.

© SMÄK, Marianne Franke

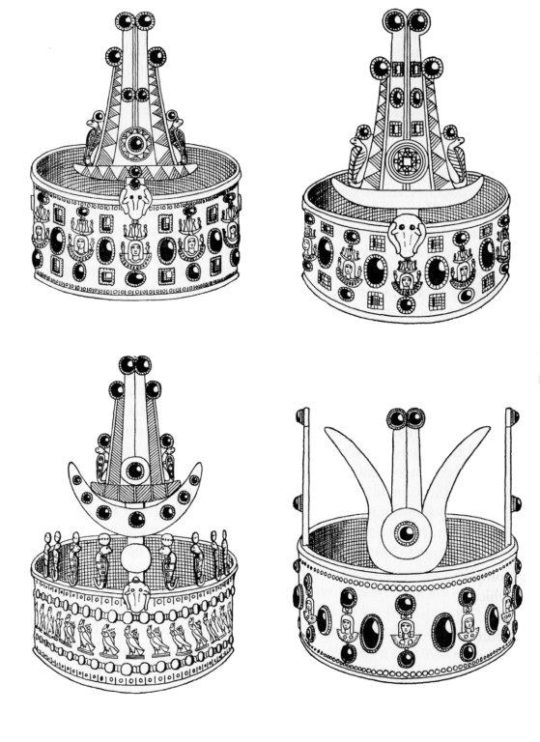

© SMÄK, Marianne FrankeThe Late Meroitic culture

After its slow dissolution (starting around 350 AD), three cultural centres became established in the area that once belonged to the Kingdom of Meroë. They are named after their most important necropolises; from north to south, they are: Ballana, between the First and Third Cataracts, Tanqasi with its centre in the Gebel Barkal area and finally the Late Meroitic culture of el-Hobagi on the Sixth Cataract.

© SMÄK

© SMÄKThe Ballana culture used to be known as X-Group. Their rulers’ large tumulus tombs are impressive as are their precious grave goods: crowns and jewellery of silver with inlays of glass and semi-precious stones, and lamps and censers of bronze. In the necropolis of Qustul, horses were buried with rich harnesses (now exhibited in the Nubian Museum in Aswan). Though large necropolises from the Tanqasi culture have survived, the grave goods are poor. The culture of el-Hobagi seems to be very much in the Meroitic tradition. High-quality bronze vessels with incised decoration are typical grave goods. However, here, too, the tradition of pyramid tombs was abandoned in favour of tumulus tombs, extending the continuity of this form of interment from the 4th millennium BC well into the first millennium of the Christian era.

By the beginning of the 6th century AD, three independent kingdoms had emerged: The Kingdom of Nobatia with its capital at Faras, the Kingdom of Makuria with its capital in Old-Dongola and finally Alodia with Soba (south of Khartum) as its capital. Finds and grave goods with Christian motifs, especially from Ballana, show that the new religion had already set foot in Nubia, though it probably started with a few isolated believers, as illustrated by the episode from Acts which mentions the Christian steward of a Meroitic queen.

Christianity in Nubia

The christianisation of Egypt by Byzantine missionaries (which was mostly politically motivated), was about simultaneous with the closing of the last Egyptian temple in Philae around 540 AD. Nobatia was the first of the Nubian kingdoms to adopt Christianity under the guidance of the priest Julian in the year 543; his work was later taken up by Longinus. The latter later went on to Alodia by invitation of its monarch, who was baptized in 580 AD.

Julian and Longinus were both Monophysites – they followed the doctrine of the Egyptian Copts postulating the single nature of Christ – whereas the Kingdom of Makuria belonged to the Dyophysite faith, the doctrine of a double nature. Once Nobatia and Mankuria merged at the beginning of the 8th century, all of Nubia finally belonged to the Coptic Church: all Nubian bishops were chosen by Alexandria. The main centres of the Nubian Church were Old Dongola and Faras. Faras became famous mostly through the Polish excavations of the cathedral and bishop’s palace with their large-scale paintings. Faras disappeared under the waters of the Aswan High Dam, though the paintings and some architectural elements (columns, capitals and architraves) are on display in the National Museums of Khartoum and Warsaw.

The Arab invasion of Egypt in 641 was stopped at the border to Nubia; a second assault in 652 led to an accord which guaranteed the Christian Nubian kingdoms their independence. It held for half a millennium: a period of prosperity, the last bloom of an independent Nubian cultural tradition that had lasted for more than five thousand years.